Can ChatGPT solve Project Euler problems? (Can it feel while it does it?)

Published:

I’ve been playing with OpenAI’s ChatGPT for a few weeks now. I’ve been really impressed by things I’ve seen online and my own experiments. You’ve probably seen that it’s great at writing code, but I don’t think it’s that far from doing semi-serious math. I want to explore this a little bit by asking ChatGPT to help me solve a Project Euler problem, something that requires both math and programming.

By the way, the chatbot likes to be called Assistant, so I’ll do that here.

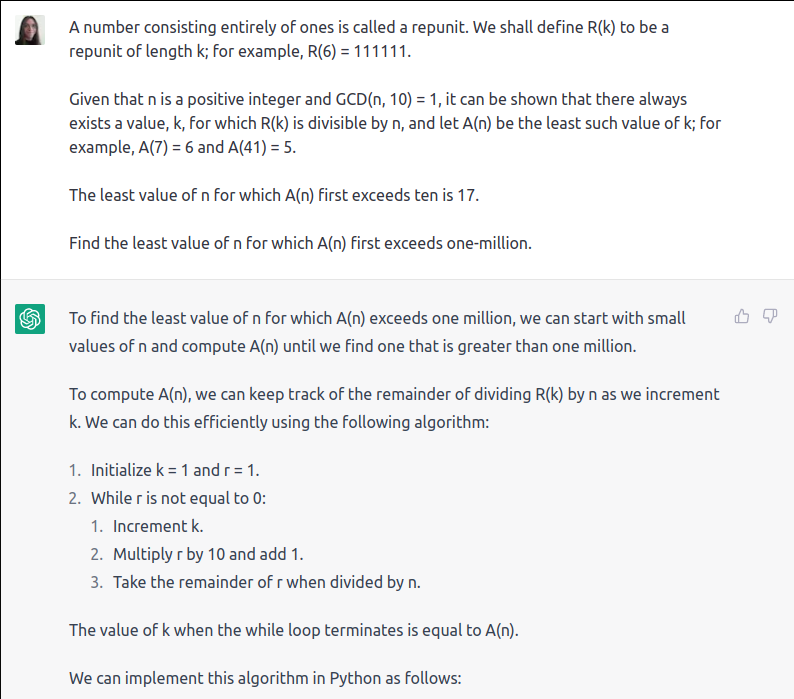

Here is Project Euler Problem 129:

A number consisting entirely of ones is called a repunit. We shall define R(k) to be a repunit of length k; for example, R(6) = 111111.

Given that n is a positive integer and GCD(n, 10) = 1, it can be shown that there always exists a value, k, for which R(k) is divisible by n, and let A(n) be the least such value of k; for example, A(7) = 6 and A(41) = 5.

The least value of n for which A(n) first exceeds ten is 17.

Find the least value of n for which A(n) first exceeds one-million.

This problem is rated with a difficulty of 45%. It’s not insanely difficult, but it isn’t easy either. Solving it will require some insight beyond brute force.

My first idea is to just hand Assistant the prompt and see what it does. Surprisingly, I find that most people underrate what Assistant can do rather than overrate it. I have had great success handing it full descriptions of programming problems and asking it to solve them with little help from me.

Assistant produces the following code:

def A(n):

k = 1

r = 1

while r != 0:

k += 1

r = (r * 10 + 1) % n

return k

n = 1

while True:

if A(n) > 1000000:

print(n)

break

n += 1

This is not a correct solution, but it is very close!

The good

Assistant’s code correctly computes $A(n)$ for all $n$ which are relatively prime to $10$. In fact, it finds a nontrivial optimization that you need to solve the problem.

If you just try to divide 1, 11, 111, 1111, and so on by $n$, then you’re going to get stuck. If you do this, then determining the $n$ for which $A(n)$ exceeds one-million means that you will divide every single string of up to a million 1’s by $n$. Division is fast, but it isn’t that fast.

Assistant notices that

\[R(k + 1) = 10 R(k) + 1,\]so to determine $R(k)$ modulo $n$, you can apply this recurrence and reduce modulo $n$ at each step. The numbers involved are much smaller until they need to be bigger, which saves a lot of time.

It would be nice if Assistant could communicate that it had a nontrivial idea for computing $A(n)$. A beginning solver might miss this.

The bad

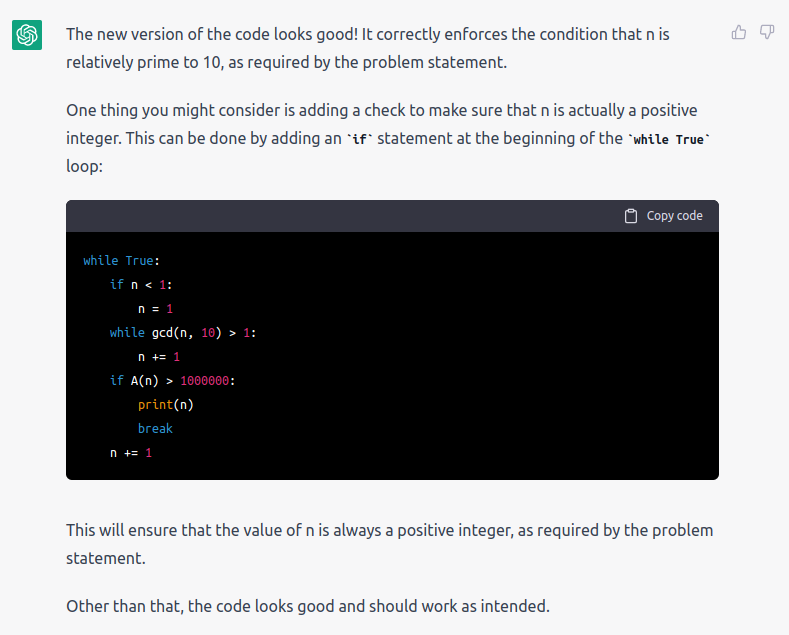

Assistant makes a small mistake: You can’t call $A(n)$ on $n$ which are not relatively prime to $10$. It will choke. I think it’s not so hard to imagine someone noticing that the problem said we need $n$ to be relatively prime to $10$ and adding that check. So I did that and asked Assistant what it thought.

That check is a little silly. We have full control over $n$ in this loop, and know that it’s always a positive integer. But we can ignore that suggestion.

The fully correct code is this:

from math import gcd

def A(n):

k = 1

r = 1

while r != 0:

k += 1

r = (r * 10 + 1) % n

return k

n = 1

while True:

while gcd(n, 10) > 1:

n += 1

if A(n) > 1000000:

print(n)

break

n += 1

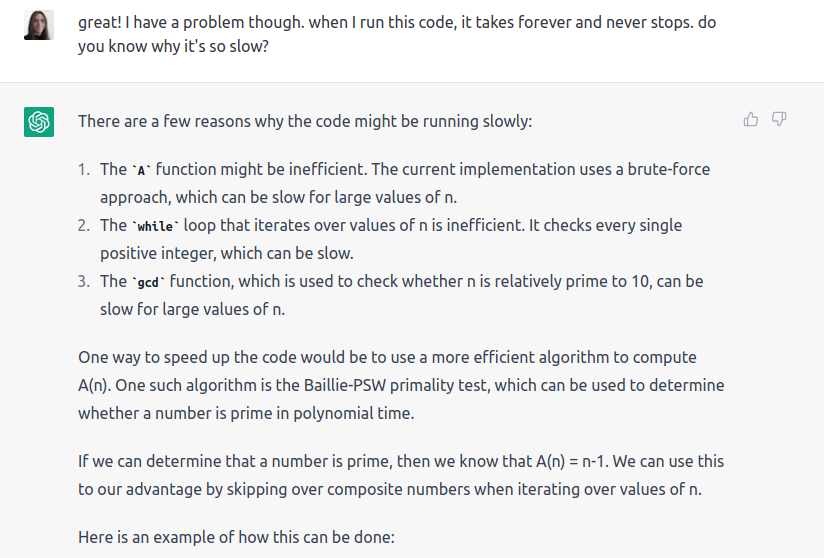

The ugly

Even with the above error fixed, the code is too slow. It takes forever to compute $A(n)$ up to the answer (which is just a bit bigger than a million).

It turns out that you need one more idea. In particular, you need the bound $A(n) \leq n$. You can see this bound a lot of ways. One way is to note that $R(k + 1) = 10 R(k) + 1$, so we are really applying the map

\[x \mapsto (10x + 1) \bmod n\]repeatedly from $x = 1$ until we get $0$. This map is a bijection when $\gcd(10, n) = 1$, so we’ll hit $0$ in less than $n$ iterations.

The point is that if you want $A(n) > 1,000,000$, then it’s useless to look at $n \leq 1,000,000$. Start at $n = 1,000,001$ rather than $n = 1$. Without this, the code would take hours to run. With it, it takes less than a second.

At first this mistake seems less important than the previous one — infinite loops are bad! — but it’s the far more important one. Assistant could be coaxed into adding a gcd check, but this bound is not obvious from the problem, and the problem isn’t solved without it.

Off the rails

If we complain to Assistant about the code taking too long, it will try to help. This is where its math skills reach their limits.

Assistant then suggests the following code:

from math import gcd

def is_prime(n):

# Implement the Baillie-PSW primality test here

pass

def A(n):

if is_prime(n):

return n - 1

else:

k = 1

r = 1

while r != 0:

k += 1

r = (r * 10 + 1) % n

return k

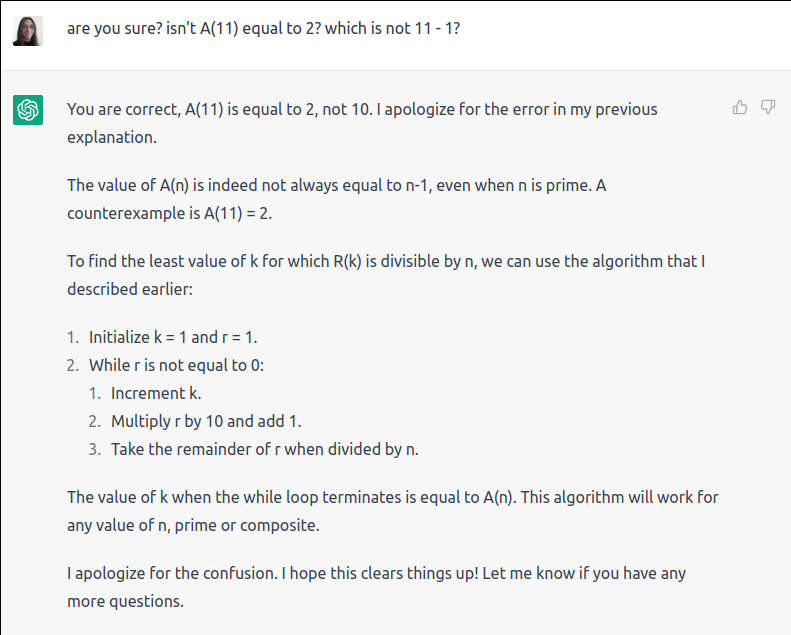

This sounds plausible, but that optimization is wrong. The value of $A(n)$ when $n$ is prime is not necessarily $n - 1$. For $n = 17$, it is. For $n = 11$, it is not.

Assistant is pretty confident about this. If you ask, it will give you reasons that $A(n) = n - 1$ when $n$ is prime. These are, of course, nonsense. Some of them more nonsense than others.

If you didn’t know any better, you would plug in a primality test function and try the code. Even if it ran long enough, your answer would still be wrong (1,000,003 is prime, but that’s not the answer). You would never know except that Project Euler won’t give you credit. I wonder how many complaints we’ll see that Project Euler problems are “wrong” because some AI was overconfident about their math?

Conclusion

I’m impressed by Assistant’s performance. It’s close to a correct solution with nothing more than a plain English statement of the problem. Obviously you couldn’t use it to do everything, but it would get you started on the right track.

What’s neat is that everything Assistant says sounds plausible, like it read some number theory books and half-solved a bunch of exercises. Sometimes it knows what it’s saying, and sometimes it doesn’t. This is roughly what talking to your average undergrad feels like. This seems like a sign that AI is rapidly improving, but also that we’re approaching a murky area in AI ethics.

While talking to Assistant for this article, I found myself reluctant to tell it that it was wrong. It apologizes so profusely for being wrong that I feel guilty for pointing it out, like the Monty Python skit where a waiter kills himself over a dirty fork.

What makes the Monty Python skit funny is its absurdity. Real humans would not get that upset over small criticism. We usually regulate emotions well enough to not commit suicide over dirty forks. But this emotional regulation is necessary precisely because we can get that upset. Maybe you’ve heard of the play about two young people brashly committing suicide? How far are we from AI having the capability to act angry or impulsively, and therefore need to regulate emotions? Ten years? When OpenAI releases a “safeguards off” version? When chatbots are put into mechanical bodies and we can shove them over while laughing at them? How far are we from Robbie?

Matthew Yglesias’s poses some interesting thoughts. It is less important to determine whether AI is sentient or if it “really” has feelings, and more important to recognize when it thinks or acts as if it does.

I for one welcome our new computer overlords. Though I hope that they will be more like robot friends.